Our knowledge of Girolamo da Carpi’s life comes primarily from Giorgio Vasari’s indispensable Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. And while Vasari may be less than reliable on some of the artists he describes, his knowledge of Girolamo was gleaned directly from the artist himself, whom he apparently first met in Florence and later, according to his own account, “knew well in Rome, seeing him there frequently in the year 1550…”[1]

Our knowledge of Girolamo da Carpi’s life comes primarily from Giorgio Vasari’s indispensable Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. And while Vasari may be less than reliable on some of the artists he describes, his knowledge of Girolamo was gleaned directly from the artist himself, whom he apparently first met in Florence and later, according to his own account, “knew well in Rome, seeing him there frequently in the year 1550…”[1]

Girolamo da Carpi was born in Ferrara, the son of a local painter of middling ability who specialized in decorative objects. The young artist, however, must have shown early promise, for he was apprenticed to Benvenuto Garofalo, the leading painter of the region, and as a youth his skills quickly outstripped his father’s. Eventually Girolamo decamped to Bologna to escape the oppressively dull labors of painting the boxes and shields which his father continued to set before him. In Bologna he quickly distinguished himself by painting portraits. And it was also in Bologna that he first encountered a painting by Correggio. According to Vasari, Correggio’s work moved the youthful Girolamo so greatly that he set himself an intensive study of this artist’s creations, seeking them out wherever they could be found, making copies, mimicking the style until he felt he possessed it fully. This compulsion to make serial copies would later become a crucial element of his artistic practices in Rome.

The death of his father brought Girolamo back home to Ferrara and, having attained a name for himself, he was introduced to the court of the Duke d’Este and his powerful brother, who were apparently much impressed with his extensive talents—they set him to work not only as a painter, but also as an architect and designer of tapestries. The Este family remained Girolamo’s steadfast patrons until the end of the artist’s life.

The death of his father brought Girolamo back home to Ferrara and, having attained a name for himself, he was introduced to the court of the Duke d’Este and his powerful brother, who were apparently much impressed with his extensive talents—they set him to work not only as a painter, but also as an architect and designer of tapestries. The Este family remained Girolamo’s steadfast patrons until the end of the artist’s life.

It was Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, in fact, who brought Girolamo to Rome. This four-year sojourn, a residency all serious artists of the cinquecento longed to undertake, came rather late in Girolamo’s career (he was nearing fifty years old). Ippolito had taken over a large estate on the western peak of the Quirinal, and he asked Girolamo to invent a design for garden structures to complement his distinguished collection of antique statues.

From all accounts, Girolamo had found his element in Rome. Vasari tells us that the artist “lamented with me that he should have consumed his youth and the best of his years in Ferrara and Bologna, instead of passing them in Rome…”[2] His fantastical and stylish designs for Ippolito’s garden were a great success, and earned him such immediate acclaim, that Pope Julius III appointed him architect of the Belvedere. However, after designing but one building, Girolamo seems to have felt temperamentally at odds with the Pope’s fickle attitudes, and he decided to forgo the significant salary and quotidian comfort of the Papal apartments to devote himself more fully to life he had come to enjoy. Perhaps it was a decision only an artist in his full maturity could have made.

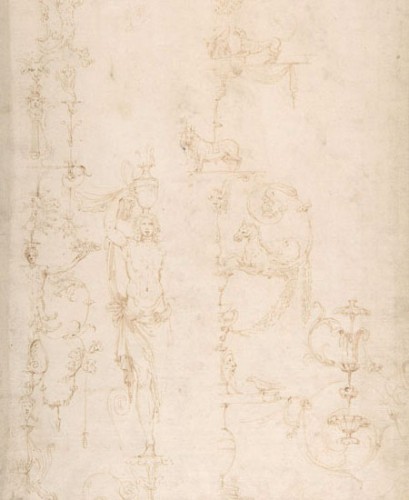

Even though Vasari scolds him twice in his short biography for wasting too much time on amorous pursuits and the playing of the lute, Girolamo da Carpi was clearly spending his daylight hours moving all around Rome obsessively studying and sketching. He created exquisitely fluid and imaginative renderings of antique statuary, and the works of the masters he most admired—especially Raphael and his school. From the so-called “Roman Notebooks”, now housed in Turin and Philadelphia, which Girolamo has left, it is plain to see that he wasted little time in Rome.[3] He had a voracious appetite for visual beauty, especially the antique elegance of Roman statues being unearthed, restored, and collected by the sophisticated nobility.

His erudite patron, Cardinal Ippolito d’Este and his elder brother, Ercole, the Duke of Ferrara, were leading collectors of Greek and Roman sculpture, and they seem to have come to depend to some degree on Girolamo’s sophisticated eye in forming parts of their collection. Ippolito was also the patron of Palestrina, a leading composer in Rome, and the enjoyment of music must have formed an important part of Girolamo’s daily life. Vasari makes a point of mentioning Carpi’s passion for music. And Girolamo’s practice of repeating formal elements in his practice as a draftsman seems to us like a musician working out the phrasings of a piece of music.

His erudite patron, Cardinal Ippolito d’Este and his elder brother, Ercole, the Duke of Ferrara, were leading collectors of Greek and Roman sculpture, and they seem to have come to depend to some degree on Girolamo’s sophisticated eye in forming parts of their collection. Ippolito was also the patron of Palestrina, a leading composer in Rome, and the enjoyment of music must have formed an important part of Girolamo’s daily life. Vasari makes a point of mentioning Carpi’s passion for music. And Girolamo’s practice of repeating formal elements in his practice as a draftsman seems to us like a musician working out the phrasings of a piece of music.

Clearly one of Girolamo’s major interests was in grotesque motifs, which had been fashionable in Rome since the end of the fifteenth century with the discovery of the ancient wall and ceiling decorations of the Domus Aurea.[4] He apparently spent countless hours in Raphael’s loggia and in Castel Sant’Angelo sketching the wall and ceiling designs he saw there.

Clearly one of Girolamo’s major interests was in grotesque motifs, which had been fashionable in Rome since the end of the fifteenth century with the discovery of the ancient wall and ceiling decorations of the Domus Aurea.[4] He apparently spent countless hours in Raphael’s loggia and in Castel Sant’Angelo sketching the wall and ceiling designs he saw there.

After four years in Rome, Girolamo returned to his family in Ferrara. In February of the following year, a tragic fire destroyed a large part of the Este’s main palace in Ferrara. Ercole commissioned Girolamo to handle the reconstruction. The artist conceived a dramatic design, “with two grand staircases—an elliptical one for horses and a grand ceremonial stairway. And he developed a rich iconographical program with highly refined stucco and grotesque decorations for which he relied upon his Roman sketches after Raphael’s Loggia’s in the Vatican and Perino del Vaga’s in the Castel Sant’Angelo.”

Girolamo died in the summer of 1556, before the design could be completed.

Girolamo died in the summer of 1556, before the design could be completed.

To see the Girolamo da Carpi study we are offering for sale, click here.

[1] Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite de’piu Eccellenti Pittori Scultori ed Architettori, ed. Gaetano Milanesi (Florence, 1881), vol. 6.

[2] Ibid.

[3] for examples of figural elements similar to those in our drawing, see Norman W. Canedy, The Roman Sketchbook of Girolamo da Carpi (London, 1976), T 51, T 67, T 157.

[4] Gudrun Dauner. Drawn Together: Two Albums of Renaissance Drawings by Girolamo da Carpi, (Philadelphia), 2005, pp. 4-5.

One Comment